Tesla's Vindication: How 1980s Principles Explain 2020s Manufacturing Dominance

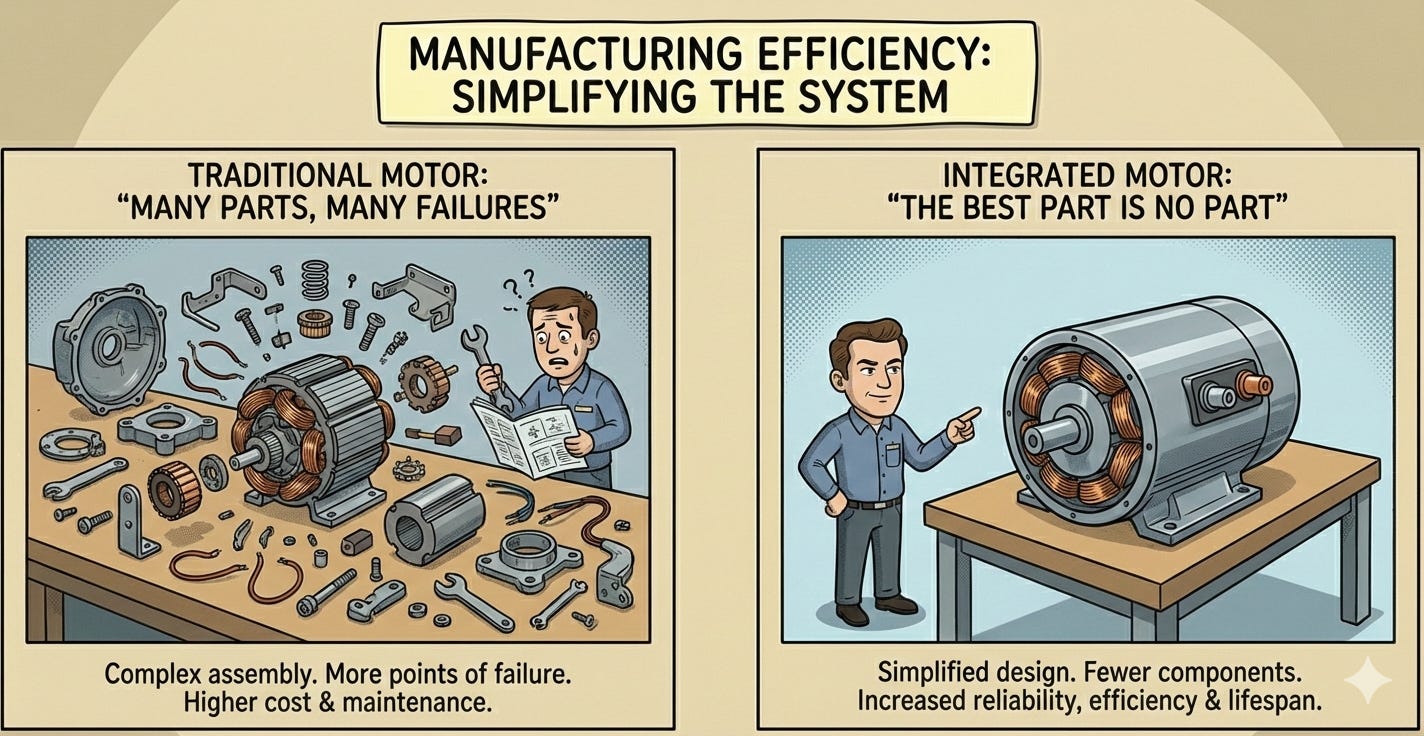

“the best part is no part”

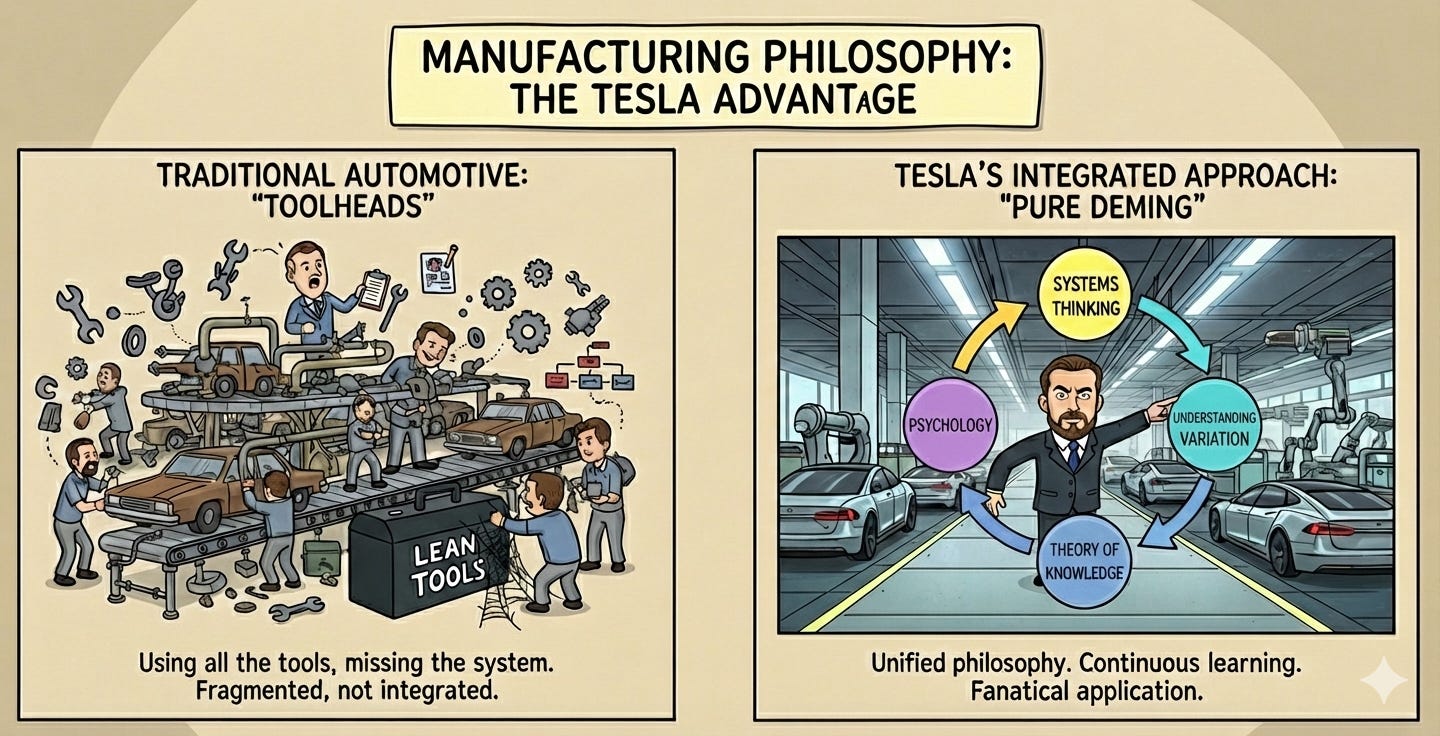

We’ve explored Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge: systems thinking, understanding variation, theory of knowledge, and psychology. These ideas emerged in the 1980s as Western manufacturing was in crisis. Japan had mastered them. America was scrambling to catch up.

Forty years later, most automotive manufacturers still haven’t caught up. They implemented “lean” as programmes and initiatives. They hired consultants. They used the tools. But they didn’t transform their thinking. Most manufacturers, as John Seddon would say, have become “toolheads” using the tools but not understanding the philosophy, therefore missing out on most of the potential gains.

One company did transform. Not a traditional automotive manufacturer, but an upstart founded in 2003 by people who didn’t know how cars were “supposed” to be made.

Tesla succeeded not through superior battery technology or electric powertrains - though those matter - but through superior manufacturing philosophy. And that philosophy is pure Deming, applied with the fanaticism of true believers.

The Traditional Automotive Approach

Before we examine Tesla, let’s understand what they were up against.

Traditional automotive manufacturers operate with a model perfected over a century:

Extensive outsourcing:

Make almost nothing in-house

Hundreds or thousands of suppliers for tens of thousands of parts

“Core competency” is assembly and brand, not manufacturing

Optimise each supplier relationship independently

Sequential development:

Design throws specifications over the wall to engineering

Engineering throws specifications over the wall to manufacturing

Manufacturing complains design is unbuildable

Months or years of back-and-forth

Slow iteration cycles

Adversarial supplier relationships:

Play suppliers against each other

Annual bidding wars for price reductions

Squeeze margins ruthlessly

Multiple suppliers for each part (reduce risk, increase leverage)

Short-term contracts

Departmental silos:

Design optimises for styling and performance

Engineering optimises for specifications and cost

Manufacturing optimises for buildability and throughput

Purchasing optimises for component cost

Quality inspects at the end

Each is measured on its own metrics

Quarterly financial focus:

Wall Street demands quarterly earnings

Pressure for immediate results

No patience for multi-year investments

Cut costs that don’t show immediate returns (training, R&D, maintenance)

Management bonuses tied to quarterly performance

Programme-based improvement:

Hire consultants to implement “lean”

Launch quality initiatives

Form improvement teams

Use the tools (5S, kanban, value stream mapping)

But the fundamental system doesn’t change

Management philosophy doesn’t change

This model worked when competition was limited and customers accepted mediocrity. It doesn’t work against someone who’s rewritten the rules.

Tesla’s Deming-Based Approach

Tesla approached automotive manufacturing with first principles thinking. Strip away “how it’s always been done” and ask “how should it be done?”

The answer looks remarkably like Deming’s teachings.

Vertical Integration: Control the System

Traditional manufacturers: “Focus on core competencies, outsource everything else.”

Tesla: “If it’s critical to performance, make it yourself.”

What Tesla makes in-house:

Battery cells (Gigafactories)

Battery packs

Electric motors

Power electronics

Full self-driving computer chips

Most vehicle software

Seats (unlike anyone else in automotive)

Significant portions of the vehicle structure

Their internally developed ERP system

Why this is systems thinking:

From Part 2, we learned that optimising parts doesn’t optimise the whole. When you outsource critical components, you:

Accept variation from multiple suppliers

Lose control over quality

Can’t iterate quickly (contract negotiations, redesigns)

Don’t capture learning (it stays with suppliers)

Create information barriers (suppliers protect IP)

Sub-optimise (each supplier optimises their component, not the system)

Vertical integration is the ultimate expression of “control the system”:

Reduce variation at source (single process, not multiple suppliers)

Enable rapid iteration (no contract negotiations)

Capture learning internally (knowledge compounds)

Optimise the whole (battery pack design informs cell design informs pack design...)

Break down barriers (everyone works for the same company, shared aim)

Develop, maintain and rely on your own software systems

Traditional manufacturers say vertical integration is expensive and risky. They’re right in the short term. But Deming’s Point 1 is “Create constancy of purpose” - long-term thinking over short-term profit.

The result: Tesla can change battery cell chemistry and pack design simultaneously because they control both. Traditional manufacturers must negotiate with battery suppliers for years. Tesla’s cost structure improves faster because learning compounds internally.

This is systems thinking applied ruthlessly.

Co-Located Engineering and Manufacturing: Break Down Barriers

Traditional automotive: Design in Detroit, engineering in one location, manufacturing in a cheaper location, suppliers everywhere else.

Tesla: Engineering and manufacturing are co-located at Fremont and other factories.

Point 9 of the 14 Points: Break down barriers between departments.

When engineering and manufacturing are separated:

Design creates unbuildable specifications

Manufacturing discovers problems during production ramp

Months of redesign and retooling

Finger-pointing and blame

Slow learning cycles

When co-located:

Engineers walk the factory floor daily

Manufacturing issues surface immediately

Design changes based on manufacturing feedback

Rapid iteration

Shared responsibility

Tesla’s practice: Weekly design changes based on manufacturing learning.

Traditional automotive: Design freeze months before production. Manufacturing must build what design specified, even if problematic.

The difference compounds. After 100 weeks (two years), the traditional manufacturer has the original design with minor changes. Tesla has iterated the design 100 times based on manufacturing reality.

This is Point 9 in action: remove barriers, enable cooperation, optimise the system, not the parts.

I’m currently driving my second Tesla Model 3 and there are significant improvements (like range) but the most striking thing is the number of small improvements, 50+ at least and together these make my newer car significantly better than the old one as a “package” that’s before we talk about ongoing software upgrades that improve the experience during ownership.

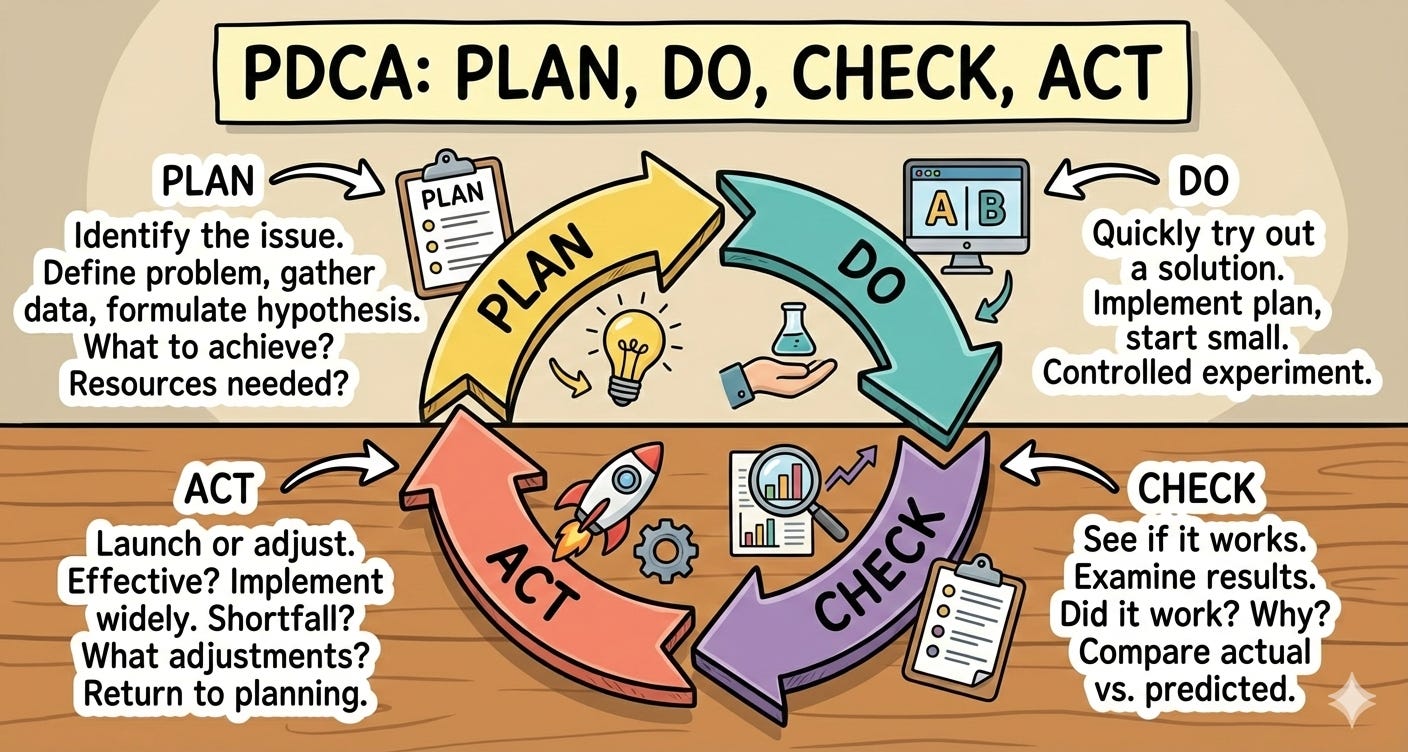

Data-Driven Iteration: Theory of Knowledge in Practice

From Part 4, we learned that knowledge comes from theory and prediction. Tesla embodies this.

Every production vehicle is instrumented:

Collect data on every component, every system, every drive

Feedback to engineering

Test theories about failure modes

Predict where improvements matter

The PDCA cycle at scale:

Plan: Theory about why a component fails or performs sub-optimally

Do: Design change, implement in production

Check: Collect data from fleet, compare to prediction

Act: Refine design, standardise improvement, identify next iteration

Traditional automotive does this over model years (3 to 5-year cycles). Tesla does it continuously.

Example: Battery pack design

Theory: Cylindrical cells with a specific cooling design will improve energy density and reduce cost

Prediction: Cost per kWh will drop by X%, range will increase by Y%

Implementation: Design 4680 cells, new pack structure

Study: Test in production, measure results

Act: Refine manufacturing process, iterate design

When wrong (predictions don’t match results), they learn quickly and adjust. When right, they scale rapidly.

This is management as prediction. This is the theory of knowledge applied to manufacturing at unprecedented speed.

Build Quality In: Cease Dependence on Inspection

Point 3 of the 14 Points: Cease dependence on inspection to achieve quality.

Traditional automotive: Design, manufacture, inspect at the end of the line, find defects, rework or scrap.

Tesla approach: Design for manufacturability from the beginning.

The “idiot index”: Part cost divided by raw material cost.

If a part costs £100 but the raw material cost is £10, the idiot index is 10. That means £90 of cost is manufacturing complexity, tooling, labour and waste. High idiot index = bad design.

Deming’s insight: You can’t inspect quality in. You must build it in through design and process.

Tesla’s obsession with the idiot index forces:

Simpler designs (fewer parts, less complex manufacturing)

Better materials utilisation (less waste)

Easier assembly (less labour, fewer defects)

Design for manufacturability (engineers think about production from day one)

· Plus, the Musk mantra “the best part is no part”

Example: Giga casting

Traditional: Dozens of stamped and welded parts for the rear underbody

Tesla: Single aluminium casting

Result: Fewer parts, less inventory, simpler assembly, lighter weight, lower cost

This is building quality in. The design prevents defects rather than trying to catch them later.

Traditional manufacturers know about design for manufacturability. But their separated design and manufacturing, their sequential development and their supplier relationships all prevent actually doing it.

Tesla’s integrated approach enables it.

Example: Tesla’s “Warp” ERP System:

Built in-house in 2012 under CIO Jay Vijayan with a small team (reports vary from 25-250 engineers). Replaced SAP entirely.

Vijayan’s explanation (2014): “Elon’s vision is to build a vertically integrated organisation where information flow happens seamlessly across departments... we couldn’t find one software program in the market that satisfied this need.”

Musk at 2023 Shareholder Meeting: “Something that people don’t really know much about is our internal applications team that writes the core technology that runs the company. We are not dependent on [third party] enterprise software... this is a very big deal... They are like the nervous system, the operating system of the company, the Tesla operating system.”

They wrote custom software for:

ERP (Warp)

Supply chain and logistics

Financial systems

Insurance business

E-commerce platform

Why this matters: SAP implementations typically take 1-2+ years and cost hundreds of millions. They’re inflexible - you adapt your processes to the software. Tesla built exactly what they needed in months, can iterate on it rapidly, and it integrates everything seamlessly.

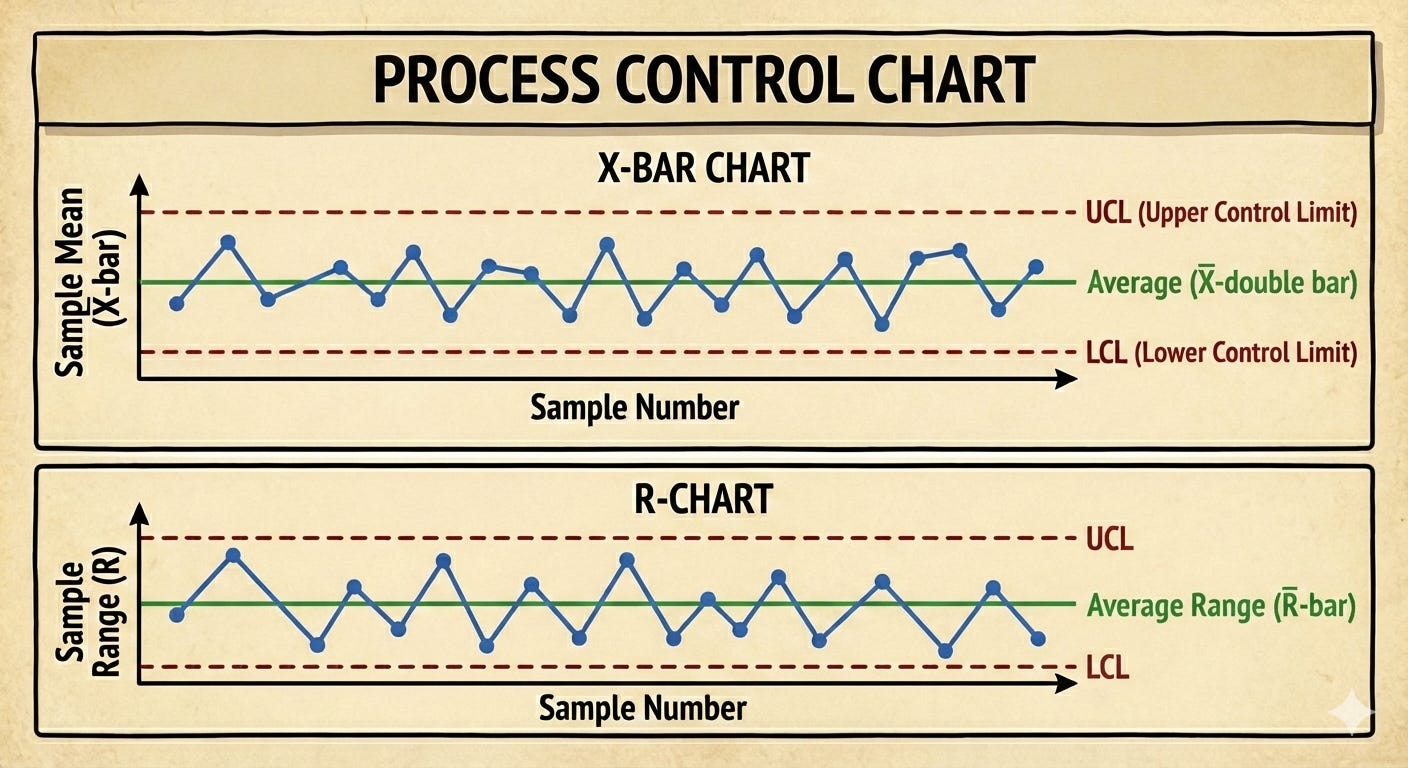

Statistical Thinking: Understanding Variation

From Part 3, we learned about common cause vs. special cause variation. Tesla applies this religiously.

Manufacturing processes monitored with control charts:

Distinguish signal from noise

React to special causes (real problems)

Don’t tamper with common causes (stable variation)

Work on reducing system variation systematically

The “5 Why’s” and root cause analysis:

Every defect is traced to its cause

Is it a special cause (fix the instance) or a common cause (fix the system)?

Systematic elimination of variation sources

Continuous reduction of defect rates

Traditional manufacturers use these tools too. The difference is culture and consistency.

In traditional automotive:

The quality department uses control charts

Production focuses on hitting numbers

When defects appear, pressure to ship anyway (quotas, deadlines)

Gaming and cover-ups (make the numbers look good)

At Tesla:

Anyone can stop the line (psychological safety - Point 8: Drive out fear)

Focus on understanding and fixing causes

No punishment for reporting problems

No arbitrary quotas that force shipping defects

The result: Variation reduces over time. Quality improves. Costs fall (less rework, less scrap, less warranty work).

This is understanding variation applied systematically.

Long-Term Thinking: Constancy of Purpose

Point 1: Create constancy of purpose for the improvement of product and service.

Tesla was willing to lose billions of dollars for over a decade building capability.

The investment period (2003-2020):

Massive losses

Wall Street scepticism

Constant predictions of bankruptcy

But steady progress on manufacturing capability

Building Gigafactories

Developing in-house expertise

Vertical integration

Iterating designs

Traditional manufacturers couldn’t make this commitment. Wall Street wouldn’t tolerate it. Quarterly earnings pressure prevented it. Management bonuses tied to short-term results prevented it.

Private company status for crucial years enabled Tesla to take the long view. Even after going public, Musk’s control prevented Wall Street from forcing short-term thinking.

What this enabled:

Battery technology development (years of investment before payoff)

Manufacturing expertise (learning compounds but takes time)

Vertical integration (huge upfront cost, long-term advantage)

Design iteration (early investments in flexibility pay off later)

By the 2020s, the cumulative advantage is insurmountable. Tesla’s manufacturing cost structure for EVs is dramatically lower than that of competitors who are just beginning the journey Tesla started 15 years ago.

This is constancy of purpose. This is patient, systematic capability building. This is Deming’s Point 1 applied with discipline that traditional automotive couldn’t match.

No Performance Reviews (Reportedly)

Point 12: Remove barriers that rob people of the pride of workmanship.

From Part 5, we learned that performance reviews destroy intrinsic motivation and create fear.

Tesla (reportedly - they don’t publicise this extensively) doesn’t do traditional performance reviews. Focus is on:

Team performance

Project outcomes

Learning and growth

Contribution to mission

Traditional automotive: Annual reviews, forced rankings, bell curves, tied to compensation.

The difference in culture is stark:

Traditional: Compete for ratings, protect turf, play politics

Tesla: Cooperate on mission, take risks, innovate

Intrinsic motivation:

Working on “accelerating the transition to sustainable energy” (purpose)

Solving hard engineering problems (mastery)

Rapid iteration and seeing impact (feedback)

Working with talented people on meaningful work (pride)

Extrinsic motivation minimised:

Not about rating or ranking

Not about pleasing the boss for review

Not about politics and appearance

From Part 5, we know intrinsic motivation produces better results than extrinsic motivation for complex work. Tesla’s approach enables intrinsic motivation.

Traditional automotive performance reviews destroy it.

The Complete Deming System

Tesla doesn’t cherry-pick Deming principles. They apply the complete System of Profound Knowledge:

Systems thinking:

Vertical integration (control the system)

Co-located functions (break down barriers)

Optimise the whole vehicle system, not individual components

Long-term thinking about capability, not quarterly optimisation

Understanding variation:

Control charts on processes

Statistical thinking throughout

Don’t tamper with stable processes

Systematic reduction of variation

Psychological safety to report problems

Theory of knowledge:

Data-driven iteration (PDSA at scale)

Predict, test, learn, iterate

Weekly design changes based on learning

Fleet data feeds engineering

Management as prediction

Psychology:

Mission-driven (intrinsic motivation)

Remove barriers (tools, resources, authority)

Drive out fear (stop production when problems arise)

Pride in work (meaningful mission, visible impact)

No traditional performance reviews

This is Deming’s 14 Points implemented comprehensively, not partially.

Why Traditional Manufacturers Can’t Catch Up

“Why don’t they just copy Tesla?”

Because you can’t copy the parts without transforming the whole. Traditional manufacturers try:

They launch EV programmes (but maintain ICE business)

They talk about vertical integration (but maintain supplier relationships)

They implement lean tools (but maintain management philosophy)

They use control charts (but maintain a blame culture)

They try to iterate faster (but maintain sequential development)

You can’t do Deming partially. The 14 Points are a system. Implementing some while ignoring others fails.

Why can’t they transform:

1. Financial system constraints:

Quarterly earnings pressure

Wall Street demands short-term results

Can’t invest billions for a decade-long payoff

Management bonuses tied to quarterly metrics

2. Organisational inertia:

Decades of established supplier relationships

Powerful purchasing departments resist vertical integration

Separated design/manufacturing resist co-location

Quality departments resist the elimination of inspection

HR departments resist eliminating performance reviews

3. Cultural barriers:

Blame culture is too ingrained

Departmental silos are too established

Short-term thinking is too rewarded

Political skills valued over engineering excellence

4. Sunk costs:

Billions invested in ICE manufacturing

ICE profits fund the company

Can’t abandon while still profitable

“Innovator’s dilemma” - success prevents adaptation

5. Management philosophy:

Don’t truly believe Deming’s principles

Think Tesla succeeded through technology or Musk's genius

Don’t see the manufacturing philosophy transformation

Want programmes, not transformation

Tesla could implement Deming completely because it started fresh. No legacy systems to protect. No quarterly earnings initially. No established departments to protect turf. Just first principles thinking about how manufacturing should work.

Traditional manufacturers are trapped by success. The system that made them successful prevents the transformation needed for the future.

The Competitive Moat

By 2025, Tesla’s competitive advantage isn’t primarily batteries or electric motors - competitors can eventually develop comparable technology.

The advantage is manufacturing capability built over 20 years through the systematic application of Deming’s principles.

The compound effect:

Year 1-5: Massive losses, capability building

Year 6-10: Break-even, early production scaling

Year 11-15: Profitable, rapid cost reduction

Year 16-20: Cost leadership, quality leadership, innovation leadership

Competitors starting today face the same 15 to 20-year journey. However, Tesla isn’t standing still - they’re continuing to improve. The gap widens.

What compounds:

Manufacturing knowledge (learning from millions of vehicles)

Design iteration (hundreds of improvements per year)

Vertical integration benefits (control costs, reduce variation, increase speed)

Culture (people who’ve been doing it this way for years)

Brand (quality reputation builds slowly)

Traditional manufacturers pursuing EVs are 10-15 years behind on the journey. They’re trying to compress it whilst maintaining their ICE business, quarterly pressures, and traditional management philosophy.

This is why Deming’s approach creates such durable competitive advantages. The difficulty is the moat. If it were easy, everyone would do it. Because it’s hard and requires patience, those who do it properly pull ahead and stay ahead.

Not Just Tesla: The Pattern

Tesla is the clearest modern example, but they’re not alone in validating Deming.

Toyota (70 years):

Applied Deming starting 1950s

Systematic continuous improvement

Respect for people

Long-term thinking

Result: Decades of automotive leadership

SpaceX:

Similar to Tesla (same leadership)

Vertical integration

Rapid iteration

Manufacturing excellence

Result: Dominant in launch services

Companies that adopted Deming successfully:

Consistent pattern of sustained excellence

Not flash-in-pan success

Compound improvement over decades

Cultural transformation, not programmes

Companies that paid lip service:

Implemented tools, not philosophy

Hired consultants, didn’t transform

Programme-of-the-month

Result: Mediocrity

The pattern is clear: Genuine adoption of Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge creates sustained competitive advantage. Superficial adoption of tools and techniques produces temporary improvements that fade.

What Can We Learn?

Most of us aren’t building car companies or launching rockets. But Deming’s principles apply at every scale:

In manufacturing:

Control the system (vertical integration where practical)

Understand variation (control charts on critical processes)

Continuous improvement (PDCA cycles)

Remove barriers (give operators good materials, maintained equipment, adequate training)

Drive out fear (psychological safety to report problems)

Long-term thinking (FSC/PEFC commitment for 20 years)

In knowledge work:

Systems thinking (optimise teams, not individuals)

Understand variation (most “performance differences” are system-caused)

Theory-driven learning (predict, test, iterate)

Intrinsic motivation (meaningful work, not ratings and rankings)

Remove barriers (bad tools, unclear priorities, political games)

In any organisation:

Ask: Are we optimising parts or the whole?

Ask: Are we tampering with stable processes?

Ask: Do we predict and test, or just trial-and-error?

Ask: Have we driven out fear?

Ask: Are we thinking long-term or quarterly?

Tesla proves these 1980s principles work in 2020s manufacturing. The principles aren’t outdated - the world just hasn’t caught up yet.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Tesla’s success is uncomfortable for traditional automotive executives to accept because it means:

Their management philosophy is wrong

Their organisational structure is wrong

Their supplier strategy is wrong

Their performance management is wrong

Their quarterly focus is wrong

The consultants they hired were wrong

It’s easier to attribute Tesla’s success to:

Elon Musk’s genius (can’t be copied)

Government subsidies (not the real reason)

First-mover advantage (ignores how they maintain their lead)

Luck (hundreds of lucky breaks over 20 years?)

But the uncomfortable truth is simpler: Tesla understood and applied Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge, whilst traditional manufacturers paid lip service to quality improvement programmes.

The difficulty of accepting this is proportional to the difficulty of fixing it. Acknowledging the real source of Tesla’s advantage requires admitting decades of wrong-headed management. That’s hard.

Easier to wait for “the EV bubble to burst”, or hope “traditional quality will win out eventually” or believe “Tesla can’t scale” (ignoring that they already did).

But meanwhile, the gap widens. The compound effect continues. The patient accumulation of manufacturing capability over decades becomes an insurmountable advantage.

The Vindication

In 1980, when Deming was finally discovered in America through the NBC documentary, management didn’t really believe him. Japan’s success was attributed to culture, cheap labour, trade policies - anything but management philosophy.

In 1986, when Deming wrote “Out of the Crisis,” the American automotive industry was collapsing but still resistant to genuine transformation. They implemented programmes, not philosophy.

In 2025, Tesla’s success vindicates Deming completely. It’s not Japanese culture. It’s not cheap labour. It’s not government policy. It’s the systematic application of profound knowledge about how organisations, manufacturing, and people actually work.

Forty years later, Deming was right. The organisations that listened and transformed dominated. The organisations that hired consultants and ran programmes stagnated.

The principles don’t age. Systems thinking, understanding variation, theory of knowledge and psychology remain as relevant as ever. More relevant, as complexity increases and knowledge work dominates.

Tesla is the modern proof. An American company, founded in 2003, applying 1980s management philosophy, dominating an industry established for 100+ years.

The vindication is complete.

Next in this series: The Deflation Engine - How Continuous Improvement Compounds into Economic Transformation

Author’s caveat, I’m not a big fan of “Elon Musk” the person; however, I remain a fan of the car company he has built, the products and the freedom he has allowed his engineers to develop them with no compromises. It’s possible to like the company but not the owner.

The bibliography for this series is at the bottom of the first post: